Guide

The Ascendient Guide to Rural Emergency Hospitals

It’s been a generation since Medicare last unveiled a new hospital type, so next year’s launch of the Rural Emergency Hospital model was bound to generate a lot of interest. Will REH status help struggling hospitals keep the doors open? In some cases, the answer just might be “yes.”

By Dawn Carter

When Rural Emergency Hospitals make their official debut on Jan. 1, 2023, it could be the biggest change to rural healthcare in 30 years – or not. More than 1,300 Critical Access Hospitals will likely study the new REH designation, but no one knows how many will make the switch.

A February study estimated that more than 600 hospitals might benefit financially from an REH conversion, but that was early in the rulemaking process, when many of the impacts were still hypothetical. In its proposed rule published July 7, 2022, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services cited a more modest projection of 68 Rural Emergency Hospitals, “though [we] acknowledge that the number of conversions could be less than or significantly greater than this estimate.”

It’s not just Critical Access Hospitals that are eligible for REH status. The new model is open to any rural hospital with no more than 50 beds as of Dec. 27, 2020.

Now that the rules are becoming clearer, rural hospital leaders can better assess the pros and cons of REH status. It’s a crucial decision with long-term implications for the health of rural communities, and we offer this Guide to highlight some of the key strategic considerations, including:

- CMS is proposing more than $3.2 million in annual facility payments for each hospital adopting the Rural Emergency Hospital model.

- Facility payments will rise each year based on the hospital market basket facility increase.

- REH outpatient services will be paid at 105% of the OPPS rate.

- Skilled nursing care may be provided as part of a distinct unit.

- Almost any new outpatient service may be offered if supported by a community needs assessment.

- On-site staffing requirements can be met with lower-paid personnel, including EMTs and or nursing assistants, provided more advanced professionals are on call.

- Rural Emergency Hospitals may be exempted from some of the Stark Law provisions that limit financial relationships between physicians and providers.

New Model, Old Problem

The Rural Emergency Hospital designation represents a once-in-a-generation effort by the federal government to shore up healthcare delivery in rural America. The last such effort came in 1997, when Congress created the Critical Access Hospital to allow cost-based reimbursement for small facilities in non-metropolitan areas.

Prior to the new law, throughout the 1980s and 90s, rural communities had lost more than 400 local hospitals. The new CAH designation attempted to halt that trend by reimbursing hospitals for the actual cost of services – rather than prospective payments – while also providing new flexibility in terms of service and staffing levels.

Thousands of hospitals took the deal and changed their Medicare status. Today there are about 1,350 Critical Access Hospitals, compared to 450 Sole Community Hospitals and 140 Medicare Dependent Hospitals, two categories previously established to address the decline in rural healthcare.

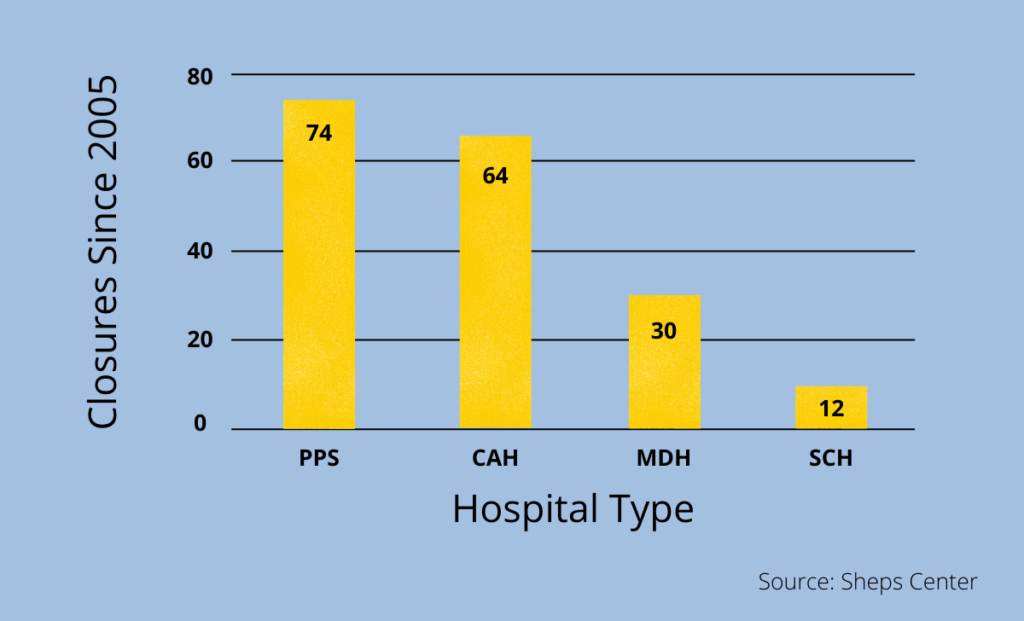

The CAH program worked well, up to a point, but the pace of rural hospital closures is now picking up. According to the Sheps Center at UNC, more than 180 rural hospitals have closed since 2005, and those with CAH status fared only slightly better than hospitals reimbursed under the Prospective Payment System (PPS).

Looking to fix the 25-year-old CAH model, lawmakers in Washington have focused on the requirement for inpatient (IP) beds with round-the-clock staffing. IP units can add tremendous overhead expense for a small, rural hospital, even as declining demand leaves the majority of those beds empty on any given night. The resulting margin squeeze can endanger the financial viability of the entire hospital.

By doing away with the IP requirement and changing the terms for Medicare reimbursement, Congress is hoping that rural hospitals can continue to provide emergency services while remaining financially solvent. REH status is “an alternative to shutting down and not having any delivery of healthcare,” according to Sen. Chuck Grassley, who co-sponsored the bill authorizing the new model.

At Ascendient, we have long argued that healthcare transformation is reducing the need for IP beds – a trend that will only continue to accelerate. In fact, years before Congress passed the legislation for Rural Emergency Hospitals, our Healthytown model anticipated the shift to more primary care and outpatient services.

But even the strongest macro trends don’t justify a one-size-fits-all approach, and certainly the REH experiment won’t serve the best interests of every rural community. To determine if REH status is right for you, we recommend four distinct levels of analysis: mission, financial, strategic, and regulatory.

Mission Considerations for Rural Emergency Hospitals

In all of the discussion around Rural Emergency Hospital conversions, “mission” is a word we don’t hear often enough. We offer it as the first consideration because, in our experience, the people who devote themselves to rural healthcare tend to be overwhelmingly mission driven.

Even if the financial model makes sense, REH status is not the right fit for a rural hospital with inpatient services at its very core. Some communities have a higher incidence of chronic conditions that require overnight hospital stays – for instance, a coal mining region with high levels of COPD. If admissions are low but steady, then shutting down IP services might have a disproportionately negative impact on the community. As healthcare management consultants, we would always look for strategic options that increase financial sustainability without undermining a hospital’s core mission.

But inpatient services carry both real costs and opportunity costs, of course. In many rural communities, hospitals offer IP services simply out of habit, even as residents struggle to find maternal health and behavioral health services. If a hospital’s mission is providing the most needed care for the greatest number of people, then underutilized IP services can run counter to the mission.

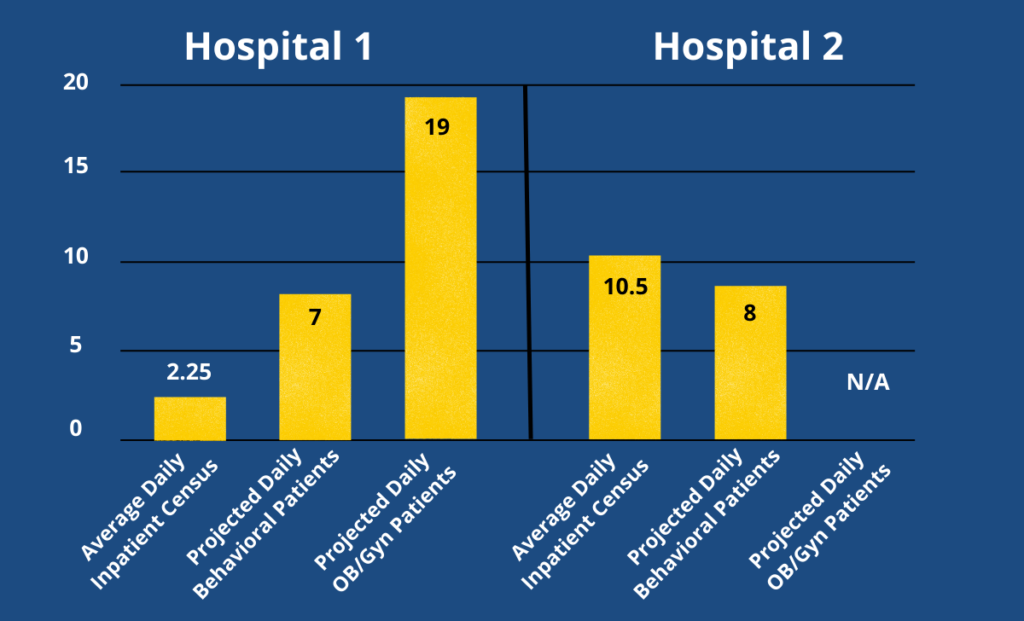

Consider this example, based on real-world data from an Ascendient client. Over a four-year period ending Dec. 31, 2020, this rural hospital had a total average daily census of 2.25 patients in both swing beds and IP beds. By reallocating the financial resources and human resources needed to serve 2.25 patients per day, our client could have served at least 7 behavioral health patients per day and/or 19 OB/Gyn patients per day.

In a county with 26,000 residents, this Critical Access Hospital might be constrained in its mission today because it must maintain IP beds at the cost of other services with greater demand.

But that won’t be true for every CAH, of course. In another rural county with only 9,000 residents, our client hospital cares for an average daily census of 10.5 inpatients. Using the same assumptions for reallocated resources, we estimate this particular hospitalcould have offered behavioral health services to about 8 patients per day. OB services are already provided by this client – both provider visits and inpatient – so the mission question would be more ambiguous. We might recommend staying the course with CAH status, provided current margins and service levels look sustainable.

The point is, before they even think about the financial details of the REH model, rural healthcare leaders should take a hard look at their mission and ask whether IP services are getting them closer to their goal – or merely getting in the way.

Financial Considerations for Rural Emergency Hospitals

As originally conceived, REH status might have been something of a no-brainer, with Medicare shelling out an estimated $30 billion to participating hospitals over 10 years. Some in Congress thought that was too high a price when Medicare was already facing insolvency, so costs were scaled back to around $10 billion before the bill was passed.

When payments begin in 2023, Medicare will pay Rural Emergency Hospitals in two distinct ways. Monthly facility payments have generated the most interest among healthcare economists because CMS will essentially pay rural hospitals to keep their doors open – something that hasn’t happened before.

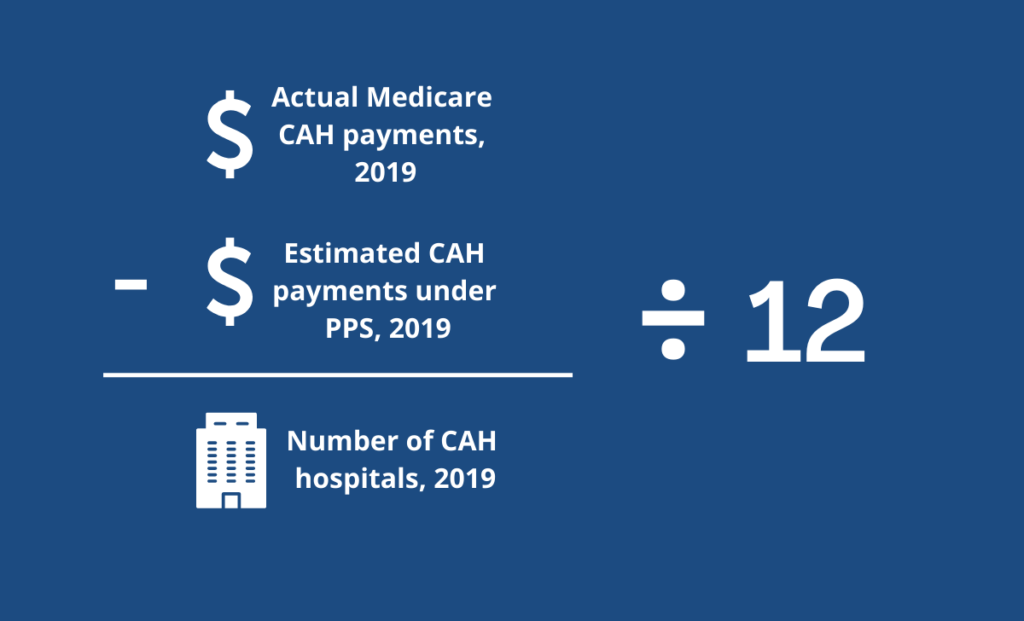

Though nothing is completely finalized yet, CMS has released a proposed figure for the monthly facility payments as well as the formula behind that number. Using 2019 figures, CMS will take all the payments made to Critical Access Hospitals (based on 101% of reasonable costs) and subtract what that figure would have been under the prospective payment system for IP, OP, and SNF services. The difference is then divided by the number of CAH hospitals in 2019 and divided again by 12 in order to arrive at the monthly payment.

One thing worth noting in that formula is the denominator. Total Medicare payments are divided by all CAH hospitals without adjusting for size. That suggests that the smallest CAHs may get a bigger financial boost from the monthly facility payment, relatively speaking.

On July 15, 2022, CMS released its proposed payment rates for 2023 hospital outpatient services. Using the formula above – with important assumptions about how co-pays are treated – CMS estimates that Rural Emergency Hospitals will receive monthly facility payments of $268,294 for 2023. That’s over $3.2 million per year as a base. In subsequent years, payments will rise by the hospital market basket percentage increase.

Here’s one way to think about monthly facility payments: The formula clearly recognizes that the prospective payment system (which REHs will opt into) is less lucrative than cost-based reimbursement (which CAHs currently enjoy). CMS is essentially writing a monthly check to help even out the difference.

Healthcare economists like Harold Wilson have argued that rural hospitals should be paid for the access they provide rather than only for volume of service. The REH model looks like a step in that direction, and we’ll be watching to see if facility payments eventually find their way into other rural models, as well, based on the reasoning that some hospital access will always be needed in rural communities.

But the financial incentive doesn’t stop there because CMS will also reimburse Rural Emergency Hospitals at 5% above the going rate for outpatient services, as established by the Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS). There was some discussion early on that only emergency services would be reimbursed at the 105% level, but CMS has determined that Congress intended to encourage the best possible outpatient care in rural communities. As a result:

“To improve access to all types of care in rural settings, CMS is broadly proposing to consider all covered outpatient department services (that is, services that would otherwise be paid under the OPPS) as REH services. REHs would be paid for furnishing REH services at a rate that is equal to the OPPS payment rate for the equivalent covered outpatient department service increased by 5%.”

After assessing community need, Rural Emergency Hospitals may also offer services that are not included under the OPPS (such as labs or rehabilitation), but those will be reimbursed under a separate fee schedule that is not subject to the 5% payment increase.

With a baseline estimate of $3.2 million in annual facility payments, rural hospital leaders can begin to calculate the financial impact of shifting from CAH to REH status simply by isolating Medicare payments for outpatient services in the prior 12 months and then comparing those same services at 105% of OPPS. Please contact us if you need help with the financial modeling for an REH conversion.

For many rural hospitals, the most basic financial calculations won’t actually solve the conversion conundrum, but it can provide an important directional signal. If your current CAH reimbursement figures are far greater than your REH projections, then you can save yourself the time and expense of further due diligence. But if the numbers are close, then you can begin to think more strategically about what an REH conversion might mean in your case.

Strategic Considerations for Rural Emergency Hospitals

If the finances make sense, broadly speaking, then the next step in evaluating Rural Emergency Hospital status is to look at the larger strategy picture. After all, the new model does involve some level of risk, because participating hospitals will no longer enjoy the predictability of cost-based reimbursement. CMS has tried to make the REH model revenue neutral compared to the CAH model, but the agency admits there is some margin for error:

“The combination of the estimated prospective payment for CAHs and the aggregate REH monthly facility payment … would be close to the amount that REH would have received from Medicare if it had decided to stay as a CAH and not convert to an REH.” [emphasis added]

Clearly REH status isn’t designed as an automatic windfall for rural providers. Facility payments plus PPS reimbursement should roughly approximate Medicare revenue under the CAH model, but each hospital will also need to factor in cost savings from cutting inpatient services plus the opportunity for additional services that bring in new revenue.

In other words, it’s complicated.

Why would any rural hospital give up the certainty of CAH reimbursement for a new and unproven approach? As healthcare strategic consultants, we propose six questions that might tip the scales. Because the following considerations are interrelated, hospital leaders should think about them holistically, not in isolation.

First, do you have the right payer mix? Medicare is likely the primary payer for IP services at nearly every Critical Access Hospital, but small differences in the overall payer mix can have a big impact on the financial calculus for Rural Emergency Hospitals.

For instance, if 70% of your inpatient population is covered by Medicare, then it may not make strategic sense to give up the sure thing of 101% cost reimbursement or may be dependent on other considerations. But what if “only” half of admissions are Medicare patients? What happens when the payer mix is more evenly split between government and non-government? In those cases, the choice of CAH or REH might not be clear cut.

Among non-government payers, do you get more patients who are uninsured/self-pay, or more who are covered by commercial insurance? Even if the numbers are relatively small in either direction, the marginal difference in coverage can have a huge financial impact on this decision.

In addition to today’s payer mix, we recommend looking at your trendline. Many rural communities are losing their traditional employer base, which pushes more patients into self-pay or uninsured status. At the same time, rural America as a whole is getting older, so many hospitals are seeing a growing share of Medicare patients. Your payer mix could look quite different five years from now, putting even more importance on the strategic choice between CAH and REH status.

Second, how important is skilled nursing care? Rural Emergency Hospitals are allowed to offer skilled nursing care as a distinct-part unit, and we have found that such services are key to financial sustainability for many of our rural clients. If a nursing home is important to your strategy and mission, then inpatient beds probably add only marginally to your costs while helping to spread the overhead. In that case, it probably makes little sense to convert to REH status. Additionally, it’s worth noting that REH status precludes swing beds, which are common under CAH status. If your hospital or system depends on swing bed access, then a conversion is unlikely to make sense for you.

Third, how efficient is your inpatient care? Most inpatient nursing ratios require one nurse for four to five patients, and if you are able to operate at that level of efficiency – with enough private payers – then you are probably generating a sustainable margin. But in many rural hospitals, the physical layout of an older facility might provide no opportunity for cross-coverage and require two nurses for a census of less than five just to meet regulatory or clinical safety standards. For those hospitals, the burden of offering inpatient services might not be justified even by the reliable reimbursement that comes with CAH status.

Fourth, what is your outlook for professional workforce availability? Rural hospitals have struggled for years to recruit and retain healthcare professionals, and the shortage grew even worse during the Covid pandemic. A well-run CAH might be able to offer sustainable inpatient services today, but the cost of 24/7 nursing and advanced practice professionals will only continue to rise.

Staffing rules for Rural Emergency Hospitals are specifically designed to offer maximum flexibility and cost savings. For instance, although an REH requires on-site staffing at all times, that requirement can be met with a nursing assistant or EMT, as long asmore advanced professionals are available on call. CMS is also offering a streamlined credentialing process for telehealth providers, making it even easier to provide important services with minimal staffing on the ground.

We believe that medical staff planning should be a major part of the discussion around REH status. Consider the age of your current professional staff and recent trends in staff turnover – remembering that shortages will only get worse.

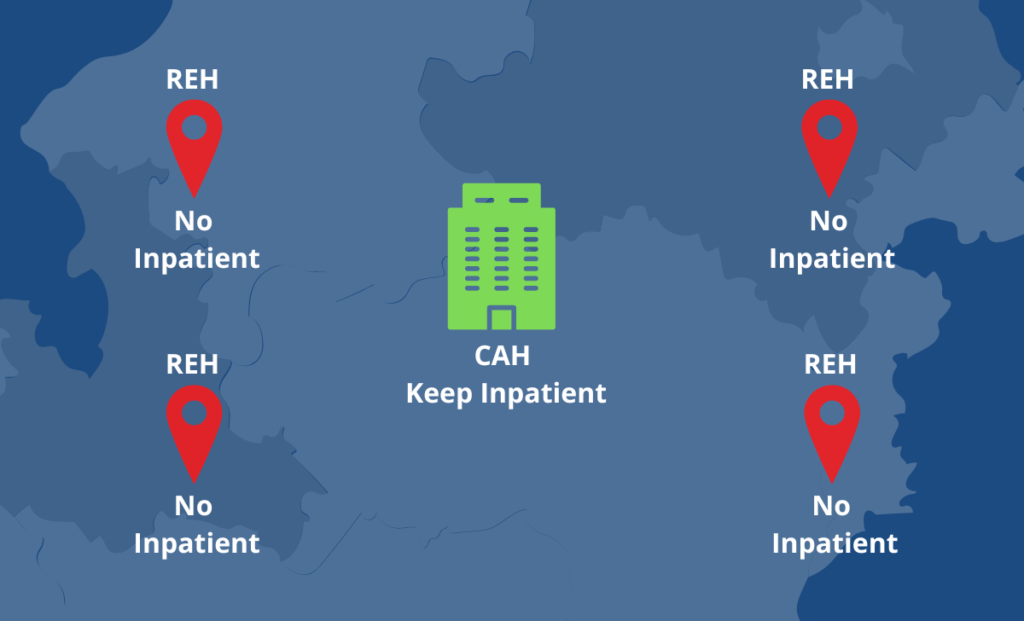

Fifth, what is your competitive position in the region? The REH model is designed to slow the trend of rural hospital closures, and we believe that $3+ million in annual facility payments will be enough inducement for many of the most vulnerable providers to make the switch.

But what about Critical Access Hospitals and small rural hospitals that are not in imminent danger of closing? We believe that some of those facilities will actually benefit by staying the course. As vulnerable CAHs drop their inpatient services, hospitals in neighboring counties will likely see an increase in demand. As of now, there is no deadline for converting to REH status, so stronger CAHs might want to bide their time (and re-think their outreach and marketing).

Finally, what new opportunities are created with REH status? The regulations surrounding Rural Emergency Hospitals run well over 1,000 pages, and CMS is likely to tweak them for months before payments start on Jan. 1, 2023. It’s easy to get lost in the legalese, but a close reading does reveal some intriguing opportunities that might come with REH status:

- The opportunity to get creative with outpatient services. When the law was first passed, some observers thought that increased reimbursement levels (105% of OPPS) would apply only to emergency services. But CMS has stressed repeatedly that almost any outpatient service would be covered as long as it meets a demonstrated community need. By offering services that differ from neighboring counties, Rural Emergency Hospitals may be able to establish a larger, regional patient base while benefitting from higher reimbursement levels.

- The opportunity to explore new partnerships. From transfer agreements to telemedicine providers, REHs will need plenty of partners to provide advanced services, and every relationship is a chance to create new revenue streams. Again, CMS has been deliberate in giving Rural Emergency Hospitals a great degree of flexibility, so it’s worth exploring partnerships that strengthen your overall financial position and sustainability.

- The opportunity for new financial relationships with physicians. In a surprise move, CMS has recommended loosening some of the Stark Law provisions that limit the financial relationships between physicians and providers. “Specifically, CMS is proposing (1) a new exception for ownership or investment interests in an REH; and (2) revisions to certain existing exceptions to make them applicable to compensation arrangements to which an REH is a party.” This could have major implications for physician recruitment and retention in hard-to-staff rural communities, so it’s a development worth following.

Regulatory Considerations for Rural Emergency Hospitals

It’s not every day that CMS creates an entirely new category of hospital, so naturally the rulemaking is a long, complex process. To help wade through 1,000+ pages of regulatory language, we reached out to Bob Wilson, a partner at Nelson Mullins Riley and Scarborough and our Rural Healthcare Initiative co-founder.

Here are the key regulatory considerations he highlighted on RHI blog, along with his summer associate Adrianne Cleven:

Rural Emergency Hospitals will provide 24-hour emergency services, observation services, and “other outpatient medical and health services.” But unlike CAHs, Rural Emergency Hospitals cannot provide inpatient services, “except those services provided in a distinct part SNF (Skilled Nursing Facility) of the REH.”

Staffing requirements vary somewhat between the two hospital types, and a key attraction of REH status might be the potential cost savings associated with lower salary expenses. Probably because of the more robust services that they offer, CAHs are required to have professional health care staff present during all operating hours – specifically, a “doctor of medicine or osteopathy, nurse practitioner, clinical nurse specialist, or physician assistant.”

For Rural Emergency Hospitals, a staff member trained in emergency medicine must be on-call at all times and available on-site within 30 minutes (or 60 minutes in frontier areas). According to CMS guidance published Jan. 26, 2023, the on-call staff member may be an MD, DO, PA, NP, or CNS. (This paragraph has been updated since the publication of the original RHI blog post.)

The new REH categorization has less stringent nursing requirements, too. The CAH rules dictate that a registered nurse, clinical nurse specialist, or licensed practical nurse must be on site “whenever the CAH has one or more inpatients.” But the REH rules – modeled after requirements for ambulatory surgery centers – only require “an organized nursing service that is available to provide 24-hour nursing services for the provision of patient care.”

Outside of the two required categories of care – 24-hour emergency services and observational services – REHs also are permitted to “provide additional medical and health outpatient services that include, but are not limited to, radiology, laboratory, outpatient rehabilitation, surgical, maternal health, and behavioral health services.”

Rural Emergency Hospitals are expected to establish the need for such outpatient services by conducting a community assessment.

Like CAHs, the rules permit REHs to serve as “telehealth originating sites” while providing an optional, more efficient alternative path to telemedicine privileging.

REHs and CAHs are held to the same standards for laboratory services, radiology, infection prevention measures, and antibiotic stewardship. And the proposed REH requirements for drug preparation, administration, and storage are identical to CAH requirements.

Conclusion

Rural healthcare is a critical part of the overall U.S. healthcare system – and one of the most critically endangered. We believe that small, rural hospitals, whether or not they currently have CAH status, should at least consider the pros and cons of adopting the Rural Emergency Hospital model.

It’s a decision that could affect the future of accessible, sustainable healthcare delivery for millions of Americans, and it goes to the very heart of our mission at Ascendient. We would be honored to serve as your advisor and thought partner as you face this once-in-a-generation choice. Please click here to learn more about our new REH Conversion Calculator, or simply complete the form below to request your free analysis.

[cta 1]

Comments