Some healthcare leaders may still have nightmares about the pandemic-era nursing shortage, when salaries for travel nurses spiked 25% nationally, wreaking havoc with hospital budgets. Those salaries have largely normalized now, but two recent changes in federal policy could create enormous wage inflation in a whole new area: nonclinical hospital employees.

These lower-skill positions – including nursing assistants, dietary aides, and environmental service workers – typically pay close to the minimum wage and don’t get the kind of management attention reserved for clinicians. But lower skill and lower pay do not signal low importance, as any patient waiting for a clean room or a warm meal can attest.

Turnover always tends to be high among entry-level workers, but we see two factors coming together to create a labor shortage in the near future. One of these factors is already generating a bit of buzz, while the other is entirely off the radar.

Immigration Policy and the Healthcare Workforce

Amid a widespread immigration crackdown, some healthcare leaders have started warning about impending provider shortages – a legitimate danger, given that approximately 55,000 physicians and 148,000 nurses are estimated to be documented non-citizens.

At least the provider shortages make headlines. Almost no one is talking about the many support roles that are heavily staffed by noncitizens, with rising deportations putting hundreds of thousands of jobs at risk. According to a recent study published in JAMA:

· About 444,000 noncitizens work as nursing aides or assistants

· About 61,000 noncitizens work as health technologists or technician

· About 58,000 noncitizens work in healthcare housekeeping roles

If the immigration crackdown continues without a carveout for the healthcare industry, some states are likely to see greater strain than others. California, Florida, Maryland, and Texas are among the nine states where at least 20% of hospital workers were born outside the U.S., according a recent study from KFF.

Tax Policy and the Healthcare Workforce

Another factor driving wage inflation is flying completely under the radar: the near elimination of federal income tax on tips. This policy change in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBA) creates a massive competitive disadvantage for healthcare employers, particularly in states where entry-level healthcare wages are comparatively low.

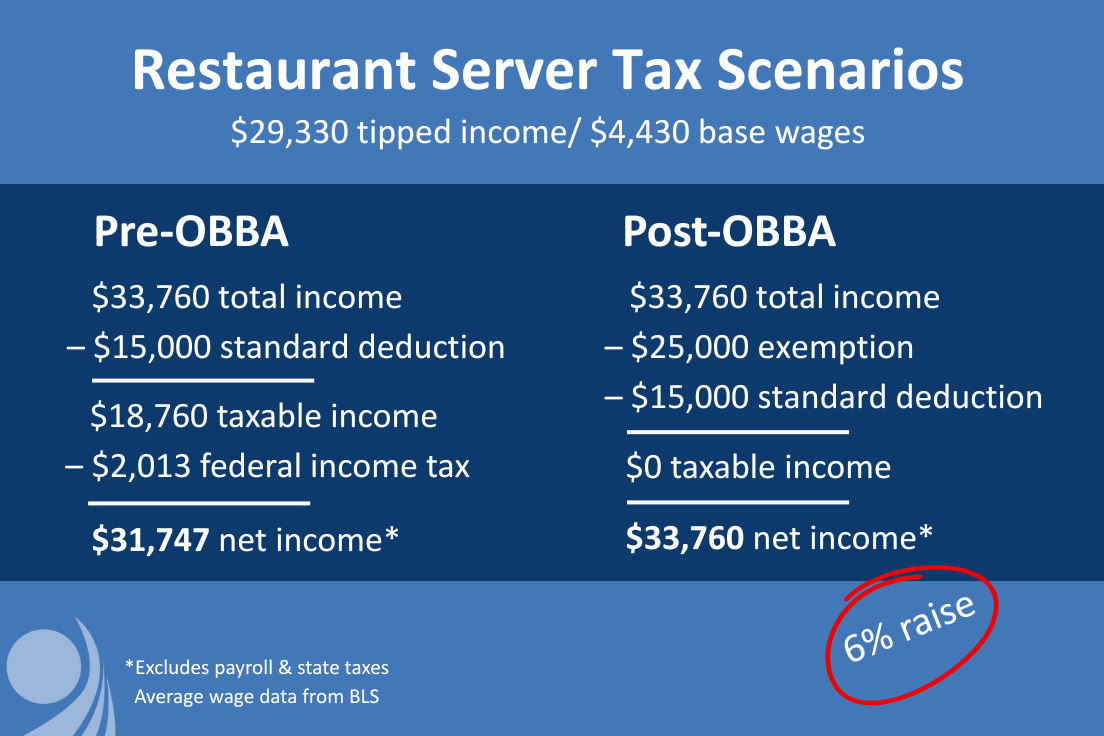

To understand the impact, consider how restaurant workers are currently compensated. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the typical server earns $33,760, including $4,430 from base wages and $29,330 from tips. Federal income taxes would look like this:

· Taxable income: $18,760 ($33,760 - $15,000 standard deduction)

o 10% federal income tax on first $11,925 = $1,193

o 12% federal income tax on remaining $6,835 = $820

· Federal income tax owed: $2,013

Between the standard deduction and the new provision that eliminates taxes on the first $25,000 of tipped income, the typical server will now pay $0 in federal income taxes rather than $2,013. That means after-tax income jumps from $31,747 to $33,760 – effectively a 6% raise with no cost to the employer. (For purposes of this example, we exclude payroll taxes and state taxes, which remain unchanged in either scenario.)

The new tax law creates immediate wage arbitrage problems for healthcare systems, especially in the South where entry-level healthcare wages are lowest. Consider the math in Texas, where nursing assistants average $35,370 annually. After federal income taxes, that nursing assistant takes home $33,164 – nearly $600 less than a restaurant server's new after-tax income of $33,760.

The gap is even more dramatic in lower-wage states. In Mississippi, where nursing assistants average just $29,660, the after-tax income is $28,139 – a staggering $5,621 less than what servers now earn after taxes. Similar disparities exist across Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, and West Virginia, where nursing assistant salaries all fall below $36,000 before taxes.

In all of these states, entry-level healthcare positions are suddenly less attractive than restaurant work – not because restaurants raised wages, but because the federal government effectively gave restaurant workers a tax-free raise. Any hospital housekeeper, food service worker, or nursing assistant can potentially earn more take-home pay by switching to a restaurant job, even if gross wages are identical.

To put it another way, industries with established tipping cultures – restaurants, bars, salons, hotels, and personal services – now offer a built-in tax advantage that healthcare employers cannot easily match. Healthcare systems will be forced to raise base wages substantially just to maintain competitive after-tax compensation, turning what should have been a targeted benefit for service workers into a hidden tax on healthcare labor costs.

Rethinking Your Workforce Strategy

The timing for all of this couldn't be worse. Healthcare systems are already operating under intense margin pressure, with many reporting negative operating margins in recent quarters. Labor typically represents 50-60% of total hospital expenses, and even modest wage inflation across hundreds of support positions can quickly escalate into millions in additional costs.

Unlike the pandemic-era nursing shortage, which was temporary and highly visible, this challenge is structural and largely invisible to healthcare leaders focused on clinical staffing. The workers affected – nursing assistants, food service staff, housekeepers, and technicians – rarely command C-suite attention, yet they're essential to daily operations.

Healthcare systems that recognize this labor market shift early will have a significant advantage in talent retention and operational stability. Those that continue treating entry-level positions as an afterthought may find themselves facing the same kind of staffing crisis and wage spiral that nursing experienced during the pandemic – except this time, there won't be federal relief to cushion the blow.

Patricia Dowbiggin and Sarah Carlson contributed research for this analysis.