Healthcare Horizons

Rural Telehealth: Re-Thinking the Timeline

By Brian Ackerman

I’ve been working recently with a provider that wants to bring rural telehealth services, including hospital at home, to the local community. After analyzing usage and mortality rates, I’m confident that telehealth offerings could be a game-changer, but there’s one major obstacle: About 25% of households in this rural county don’t have broadband in their homes.

Sadly, that’s not unusual. According to the USDA, about 22% of rural Americans don’t have fixed broadband access (and the figure rises to 27% for those living on Tribal lands).

Lack of broadband is a big problem for rural telehealth, because it takes a lot of fast data to monitor patients in their home, around the clock. Without broadband access, many people aren’t getting the medical care that would improve and prolong their lives.

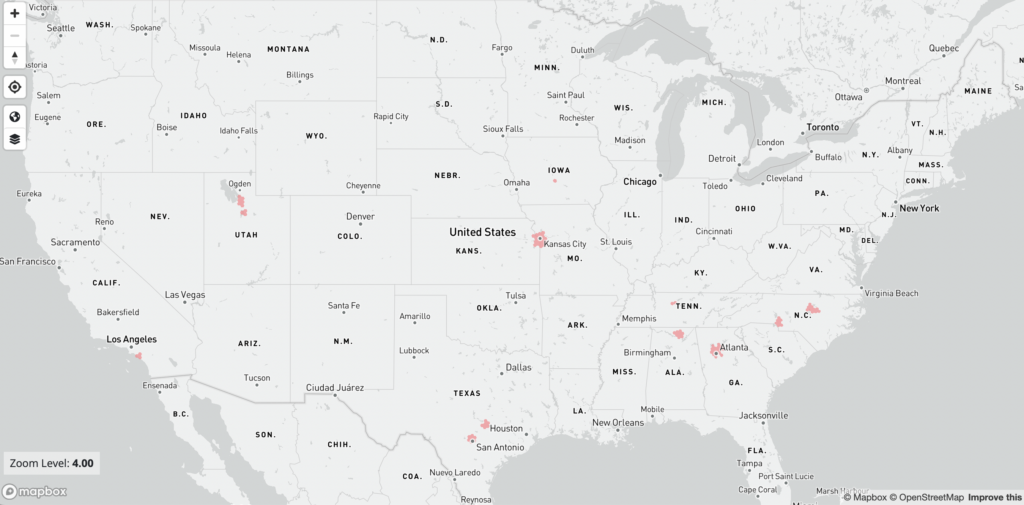

Once you realize that broadband is a matter of life and death, it’s agonizing to think about the slow pace of connectivity. Even Google, with all its billions, is barely able to move the needle on building a high-speed fiber network that covers all of America. Per the Federal Communications Commission, as of June 2022, Google’s fiber broadband coverage looked like this:

Not sure what you’re looking at? The map shows “fiber to the premises,” or in-home broadband with Google Fiber. You might have to squint to see the little pink blobs that indicate broadband access in places like Atlanta or Kansas City – and that’s exactly the point.

Google Fiber launched commercially in 2012, so it’s a little depressing to consider the slow rate of progress over 10+ years. I won’t repeat the coverage maps for other providers like Verizon or AT&T, but they aren’t much better.

For healthcare executives outside a major urban market, it might be tempting to write off rural telehealth offerings simply because fiber broadband is growing so slowly that it may not reach your town in your lifetime.

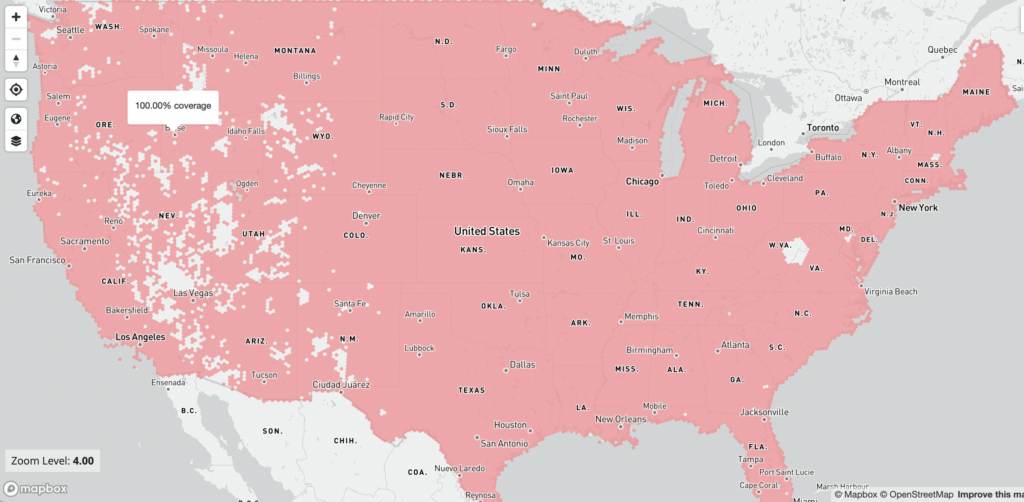

But I think that would be a mistake. You’re probably right about fixed lines, but that’s not the only way to get broadband to smaller communities. Consider this map, for instance:

What you’re looking at is the FCC coverage map for Starlink, the satellite broadband company from Elon Musk. Even last year, when the map was published, Starlink already covered the vast majority of Americans, including those in rural areas.

Of course, coverage and connection are two different things. Starlink satellites may cover vast swaths of rural America, but connecting to the system doesn’t come cheap – $599 for equipment plus $110 per month for broadband service. At those rates, only a small fraction of rural households could afford to pay for Starlink out of their own pockets.

The Future Is Looking “Up” for Rural Telehealth

Despite the price tag – and a significant waitlist – usage is rising. Worldwide, the company claims 1 million subscribers so far, and the growing customer base has taken a toll on data speeds. According to network tester Ookla, Starlink’s download speed has dropped for several consecutive quarters, and U.S. users are now seeing an average of 53 megabits per second (Mbps), roughly double the FCC’s minimum threshold for broadband.

Fiber broadband in cities and suburbs routinely offer speeds above 100 Mbps, so it’s no surprise that Starlink’s subscriber base is growing much faster in America’s non-metro counties, where broadband is otherwise unavailable. As Ookla says:

“Without a doubt, Starlink often can be a life-changing service for consumers where connectivity is inadequate or nonexistent. Even as speeds slow, they still provide more than enough connectivity to do almost everything consumers normally need to do, including streaming 4K video and video messaging.”

Is that good enough for rural telehealth? The answer probably depends on the specific application you have in mind, but in any case, Starlink promises faster speeds and greater dependability as more satellites are launched.

Those launches are happening at a breathtaking pace. Last year alone, Starlink put 1,722 new satellites into orbit – a rate of nearly five per day. With about 4,000 satellites already in use, Starlink could easily hit its regulatory limit of 7,500 satellites by early 2025. (The company says its total “constellation” could eventually reach 30,000, with FCC approval.)

To put all of that into perspective, remember that Starlink launched its first operational satellites in late 2019, so it has taken less than 3.5 years to achieve nearly 100% coverage across the US.

Google Fiber made its commercial launch seven years earlier, in 2012, so it’s pretty amazing to think about the rate of disruption that Starlink brings to the broadband industry. Says tech review site Cnet: “There’s every reason to believe that services like Starlink will reach the bulk of underserved communities long before fiber ever will.”

Who Will Pay for Rural Broadband?

Until now, policymakers have treated broadband access as an infrastructure issue, but in my thinking, it’s quickly becoming more of an investment issue. That is, we’ll soon have the technical capability to offer high-speed internet to nearly every person in America, including those living in the most remote rural areas. At that point the question becomes: Who pays for it, and how do we justify the price tag?

Yes, it’s expensive to pay $110 for home broadband, but I can envision situations where that subscription fee could be a relative bargain.

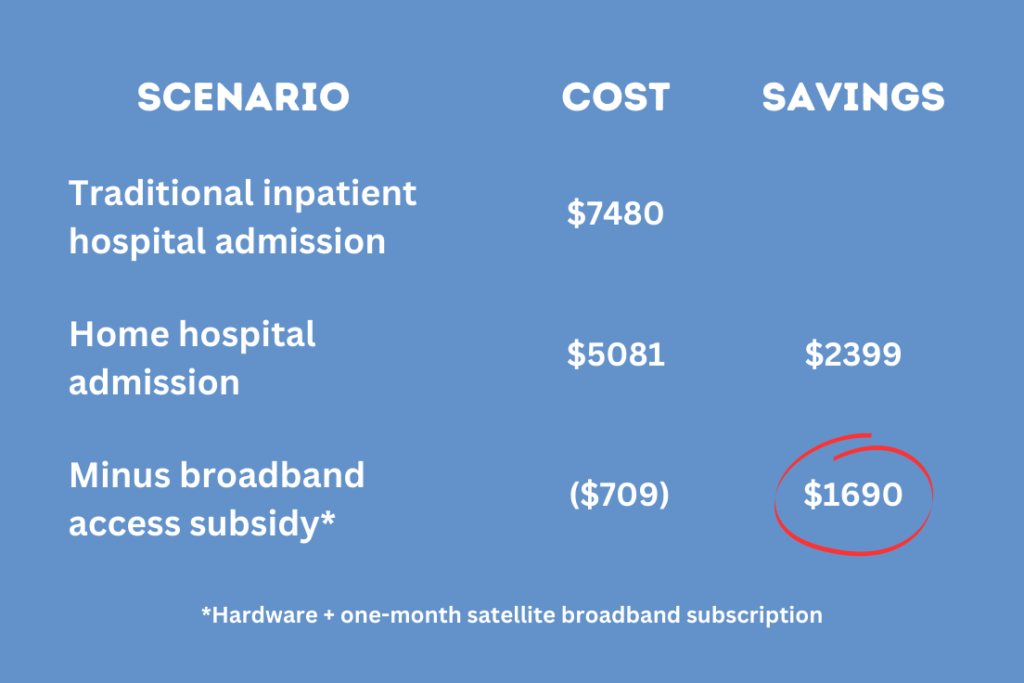

Johns Hopkins, one of the earliest pioneers of the home hospital model, found that in-home care is 32% cheaper than traditional inpatient care – an average savings of roughly $2,400 per admission. If a payer needs to invest around $700 to provide home hospital access for a rural patient ($599 for hardware plus $110 for a month of broadband), the savings are still significant.

It’s relatively easy to model the savings for an acute care episode, but the advantages of rural telehealth don’t end there. Post-discharge, patients with broadband in their home can be monitored remotely to prevent costly readmissions – an average of $15,200 per AHRQ. Longer term, patients with broadband access will benefit from more frequent, more regular telehealth visits with a primary care provider.

Increasing primary care is the single biggest driver of savings under Ascendient’s Healthytown model, but the shift is especially difficult in rural areas. In one study, researchers found that rural residents with inadequate access to primary care providers also had the lowest rates of broadband penetration. That double whammy helps to explain why rural mortality rates are 20% higher than urban mortality rates.

Unless someone has a workable plan to attract more providers to non-urban areas, telehealth is the only hope I see for increasing primary care and preventive care in rural communities.

Given all the cost savings, I have to believe that commercial insurers and Medicare Advantage plans will take a hard look at the math. Humana, for instance, has already said that it plans to “make value-based home health services available to 40% of Medicare Advantage members by 2025.”

(Ironically enough, that’s the year I expect Starlink to achieve full coverage for its current satellite constellation, so Humana could get even more aggressive with its home health goals, if access is the primary barrier.)

But why stop there? Three states already have launched Medicaid demonstration projects to pay for short-term food assistance and other nutrition programs, while another four states are working with Medicare to test medically tailored meal programs. These “food as medicine” trials have attracted support from both political parties, due in part to potential cost savings.

I think the same rationale applies to broadband subsidies. In some ways, broadband internet is an even more natural fit for Medicare and Medicaid coverage because the savings are derived from more efficient healthcare delivery today and from prevention efforts that pay off down the road.

Once you have a critical mass of payers willing to subsidize broadband for healthcare – even temporarily – then the possibilities really start to get interesting. The public health profession increasingly views broadband as a social determinant of health, so it’s easy to envision cost-sharing experiments involving health departments, hospitals, and various levels of government.

As Ascendient’s practice lead in public health strategy, that’s something I’m eager to explore further.

Conclusion

Most hospitals look three to five years out in their strategic planning. Given the recent pace of change, the basic access challenges facing rural telehealth could well be solved within that timeframe (even if speed remains an issue).

If you’re a rural healthcare leader who thought, “Never in my lifetime,” then maybe it’s time to reassess. The technology is moving so much faster than we realize – is your strategy keeping up?

PS: Elon Musk, if you happen to see this and you’re looking for a demonstration project to show how Starlink broadband can save lives in rural America, I have a few hospital executives you should meet…

Ascendient’s mission-driven consultants can provide expert guidance on rural healthcare operations and strategy. Please contact us for more information.

Comments